Art speaks with many voices. Historically, it has furthered authoritative needs (both secular and religious), strengthened cultural ties, and even served as a mouthpiece for its own sake. Since the sixties, art’s activist voice has played an increasing role in the agenda of many artists, and today continues to be as loud as it is pervasive, covering walls of galleries and art fairs and filling the pages of art magazines. The current exhibition at the Salt Lake Art Center, Liberties Under Fire: The ACLU of Utah at 50, is a collection of five nationally-recognized artists whose voices speak boldly, angrily, heatedly, ironically about humanitarian aims the ACLU has fostered. The exhibit makes me wonder if now, after 50 years of crusading for civil liberties, the voice that demanded these liberties along with the ACLU demanding these liberties has become a cacophony of polemics.

The ACLU has, since World War I, sought “to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed by the Constitution and laws of the United States.” It has successfully defended freedom of religion, separation of church and state, freedom of speech, abolition of capital punishment, access to contraception and freedom of choice for abortion, civil rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, affirmative action, immigration rights and gun control, and done so peacefully and constructively. Art that incites strong emotion with an angry voice is a substantial part of art history’s canon; it continues with full force in the post-modern, post-structural art of the contemporary landscape. But is there not a point where an open forum of pro-active ideas and ideology, a forum where artists move ahead with work is more timely for the arts community and the community at large than art that incites more anger to the uninitiated than it promotes, closing minds instead of opening them?

Kara Walker, one of America’s most widely known and popular contemporary artists, bases much of her aesthetic on her identity as an African American woman. Equality in race relations, especially for the African American community, has occupied the ACLU’s efforts from its roots. The issue of slavery has tarnished the history of numerous nations — and many to a greater extent than our own. Walker has developed her grounding in the art world by ensuring that this once epidemic atrocity will never be forgotten. Her works from the series “Harpers Pictorial History of the World,” earthy, stark silhouettes, imposed on historic lithographs, such as in the work “Crest of Pine Mountain: Where General Polk Fell,” create disturbing scenes. Walker places her silhouettes one over the other, using positive and negative spacing to great effect, in images of American slaves being brutalized.

Walker’s art is charged with the drama and terror of a period that organizations such as the ACLU and the majority of Americans are trying to put behind in order to be an integrated, unified, culturally diverse and fully functional society. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. believed this could be done and we are seeing this with the success of Barrack Obama. Kara Walker, however, cannot seem to forgive injustices of the past and move toward a greater, positive optimistic and constructive future. An artist like young, internationally respected British artist Chris Ofili, offers a counterpoint to Walker. From a country whose slave trade far surpassed our own, Ofili is embracing the beauty of his African heritage, opening minds and ears to his culture.

Despite efforts from the ACLU and various LGBT coalitions, and more realistic and positive portrayals of homosexuals in the media, homophobia has not been eradicated. Much of the stigma against homosexuality in the past has been from inaccurate portrayals and stereotyping and this has undergone a distinct change over the past few decades. John Trobaugh, in his series “Double Duty,” places Ken dolls of various races in stereotypical “gay” clothing, or lack of clothing, in poses juxtaposed against familiar sites such as the Grand Canyon. In one he even dresses two Ken dolls in drag in front of the City/County Building in Salt Lake City.

Trobaugh raises some interesting commentary on environmental expectations that affect gender identity on children, male or female, playing with dolls having an effect on their persona. However, and I say this as a homosexual male myself, beyond this, I view his art as propagating gender bias and reinforcing gender identities rather than neutralizing gender stereotypes. To a less sympathetic audience, Trobaugh’s irony has a tendency to close doors, not just to “insiders,” but to those whose minds it is really trying to open.

Enrique Chagoya’s catchy collages are bold, ironic, comic, idealistic, mocking. In his work, Chagoya uses and abuses icons and iconic figures, historic, contemporary, religious, and secular; nothing is sacred, all is profane. They are well-articulated, humorous and thoughtfully constructed visual puns with a blatantly blasphemous ideology: George W. Bush holding a stack of Bibles; Jesus Christ, Mohammed and Arnold Schwarzenegger in a single ballet tutu; or more sobering statements on Christianity. These may strike some viewers as humorous, but some seem highly didactic, and some are just in bad taste. A monkey on a cross is pushing the limit, and, again, closes doors and minds.

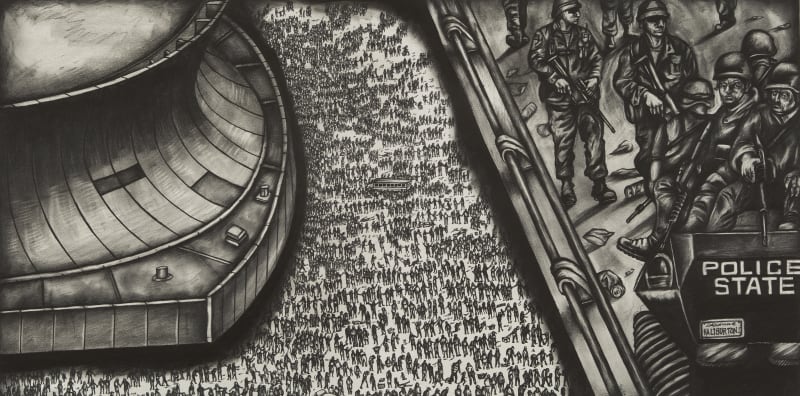

Many contemporary artists, writers, and poets push political buttons, and appropriate to an exhibit about the ACLU, these appear in Liberties Under Fire. Sue Coen presents her statement on mass injustice in works like “Thousands Trying to Escape from the Superdome.” Jenny Holzer, another internationally recognized artist featured in this exhibit, draws her political pistols and aims them on abuses of power. She replicates, on oil and linen, an actual autopsy report and letters from parents of those who have been killed in the Iraq War in her series “Torture, Imprisonment and War.” Holzer’s raised visual voice is no different in context than the inescapable polemics seen on CNN, network news, and talk radio, reminding listeners what a precarious situation we are in. Art that voices an alternative, more independently-thought ideological voice is unfortunately rare.

The ACLU has been prodigiously successful in legislating civil liberties. Liberties Under Fire is an honest exhibition with strong artists whose voices are raised alongside the efforts of the ACLU in Utah in the past 50 years. Viewing the exhibit may make you ask, as it did me, Does contemporary art that reflects these aims have to maintain an angry voice? Every voice should be heard, but is it necessary to always angrily focus on the past, or can we also use art to promote a more open, optimistic dialogue?