This article began as a review of an exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford which took place earlier this year, Artists of Radio Times: A Golden Age of British Illustration. It has become something else, partly because of events lived through during its gestation, partly because of feelings about the exhibition which took a while to resolve, but essentially because of my own evolving concept of what illustration is and can be, and the kick which both these factors gave to my thinking. So rarely does an exhibition in a major museum exclusively devote itself to illustration, that it raises high hopes. It gives ephemeral work -- scribbled-over roughs, marked-up, blotted and patched submissions -- the sort of critical attention which art seems to need to be taken seriously, and has an inevitable impact on how the profession is perceived and treated, giving it a tradition and credentials which can be helpful or burdensome, or both. This one certainly had an agenda. Unapologetically nostalgic for past practice, unremittingly negative about present possibilities, the first sentence of Martin Baker's catalogue says it all:

The tradition in Art, exemplified by the craftsmanlike drawings commissioned by Radio Times since 1923, has been, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, corrupted by ugliness and vacuity.

And it goes on in much the same vein. So the current influx of new technology is viewed as entirely destructive ("The internet will complete the dumbing down of the medium"), which seems ironic when the earlier arrival of radio and television on the scene is, in contrast, the impetus for a golden awakening, a high-point in art history which bears comparison with the Renaissance ("poetic depth found in the drawing of Raphael or Rembrandt") and the ultimate justification for the exhibition itself.

Baker is passionate about his subject, which is well and good, and indeed there were drawings here which were a pleasure to meet with. And, arguably, there is something of a golden age quality in the nature of the industry at that time: those reasonably smooth early twentieth-century career patterns -- a little work in a commercial studio or a silversmith apprenticeship, perhaps some evening classes at Heatherley's, and, bingo, regular commissions of a comfortably predictable nature everafter. But looking at the work as a whole -- over several decades, and in the context of major world events and the flux of extraordinary social change -- it seems solidly and stolidly to shore up a conservative and middle-class Britain, patronised and patronising. Period Drama vignettes reminiscent of OUP children's books. Clarinets and cellos, frollicking lambs, Christmas tree villages. History's famous men in telling little scenes. If we read Radio Times as a social document, the British public emerges gullible and childlike, interested in accessing 'Culture' and 'Education' but in a Listen with Mother sort of way, while the edginess of experimental television finds no echo in its pages. I wasn't happy with this role for illustration -- subsidiary and passive, rather than thoughtful and thought-provoking. I'm too ambitious for it as a discipline, and too aware, as we all are nowadays, of the power of the image as a vehicle for influencing unquantifiable -- but potentially enormous -- audiences. Image-makers have responsiblities, don't they?

And a few weeks later, I met Sue Coe.

(But I need to get to Sue Coe in a roundabout way, so bear with me - though I might say that when I asked her why she had left the UK in the seventies, she said that one reason had been that she hadn't wanted to end up illustrating Radio Times).

During the past eighteen months I have been involved in putting together an arts initiative for an animal welfare educational charity, Compassion in World Farming Trust. The specific brief was to get people thinking about the future of farming and, in particular, the ethics of animal biotechnology -- cloning, genetic engineering, designer animals ad infinitum. The initiative culminated in early October with an exhibition at the ICA, featuring work selected from submissions in response to adverts in the arts press and a direct mailing to art colleges. We were not at all sure what we would get, but aimed to provide a platform for anyone who wanted to make a visual statement about the new science: After Dolly was conceived as a debate which might radiate beyond the gallery.

Much of its effect, as in all speculative educational work, was bound to be intangible -- but then campaigning organisations are used to dealing with that elusive phenomenon, public opinion. What was new, from the Trust's point of view, was the invitation to artists to take hold of the debate themselves, on all of our behalfs. We took the show into the ICA as a symbolic act, as a way of saying 'these issues matter', that a debate about animal rights is worthy of being part of culture. We were asking art to engage with a pertinent contemporary issue in the way that the best editorial illustration can do, summing up/focusing public sentiment, perhaps subtly taking it forward, exposing its curious logic.

This process of moving an issue from a position of fringe interest towards general acceptance is a necessary part of all protest movements. There is typically a highly creative (often extended) first phase when the issue is taken up and developed at the edge. Art-making can be a vital ingredient, and because in a context like this it engages closely with what its makers are saying and thinking and doing it tends to have an illustrative bent. Where I live in East Oxford, there is a strong green presence, reflected constantly in street and graffiti art, Adbuster-style interventions, and a cult of the recycled and low-tech which merges very creatively with new-tech know-how. People who would never think of themselves as illustrators begin to practice illustration because it is an instinctive form of communication and they want to get their message out. At a national level, at the recent Stop the War march (a real coming-together of issues and protest groups), Palestinians and Israelis, Socialist Workers and New Age Hippies made their message visual on handmade placards and banners, with personal annotations, drawings and stitchings. Message art .

John Berger has written in connection with cave paintings, the earliest art form known to us, that art emerges fully formed: it is made out of necessity. Protest of necessity produces illustration. Or we might turn this round and say that illustration is a powerful tool for protest.

This perhaps needs restating in a cultural climate that is preoccupied with self-promotion and self-analysis. YBA is notoriously narcissistic, even when it seems to be getting at something broader. Tracy Emin touches on racism and Feminism, but as part of her life story. Hirst has been linked to animal rights, and in a sense he does do animals, but in a sensational, attention-grabbing sort of way, rather than to make a point (in fact he consistently shuns the idea that his work has any point: fags and corpses, they're all the same). Beyond the self-styled avant-garde, cultural initiatives are even less likely to tackle issues in a way that encourages debate, but tend to follow the current fashion in political correctness. At the moment, rural issues are in vogue, but essentially from a pro-farming perspective. Love, Labour and Loss, an exhibition targeted at the two worst-hit Foot and Mouth areas, Cumbria and Devon, and featuring livestock in art from Pastoral to pyre, is a rather patchy survey of man's relation to beast as it figures in the art of the last 300 years, and scarcely glances at the big awkward questions which an exhibition about animals in art surely needs to raise at this time -- questions which surfaced during Foot and Mouth, but without proper airing (for a counter-blast, try Sue Coe's reportage work about American meat production, Dead Meat).

Art is, as we all know, a means of opening ourselves up to new ways of thinking, of taking us outside our own narrow experience of the world. High-profile Fine Art at the moment is self-obsessed and self-promoting. Cultural patronage -- whether in the form of sponsorship from individuals, government bodies or even educational trusts -- comes with all sorts of baggage and an agenda. But illustration? An illustrator knows how to take a message out and make it function in all sorts of contexts, to communicate information succinctly and vividly, to create an image which elucidates a complicated text or stands in its place. He/she is content to be part of, and to serve, a process which is above and beyond his/her own artistic persona. An illustrator with a mind to do so can make work which may radically enhance the possibility for debate in this superficially democratic but indisputably poorly-informed western society of ours.

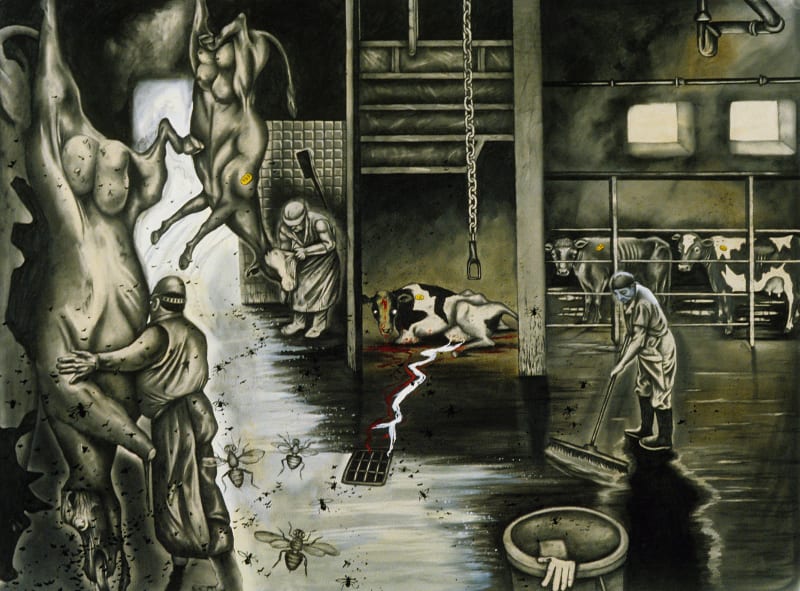

In the middle of After Dolly, Sue Coe showed some slides of her work and spoke about her experiences as an animal rights artist. We crammed in between white plinths, sat on the floor cross-legged, bent our necks back to get a view of the screen. All the time she was speaking no one moved or spoke. The texts on her images lifted out into the room. We were put in the picture, whether it was a pair of birds' experience of September 11, or the hour in which a (literally) broken cow awaited her slaughter while the workers went to lunch. [Meat Flies, left].

I looked back subsequently at some of Coe's eighties work, products of the Thatcher-Reagan, England is a Bitch era. Apartheid, the Nuclear Arms' Race, striking, bloodied miners. Homelessness, gang rape, vivisection. So many injustices. So many everyday table-top victims. It is a commentary on the time like no other -- apocalyptic, seemingly inconsolably hopeless, and yet embodying the will to turn things round in the very fact that it was made. Donald Kuspitt has emphasized duality in Coe's work on a number of counts: how it strides the divide between, on the one hand, 'high' gallery art and on the other, interventionist social commentary working "within the social life" through books, newspapers, billboards, now the Web, to infiltrate and disrupt cultural assumptions. You can visit Coe's copious website and buy her books and prints (some prints are sold for the benefit of In Defense of Animals). You can view her drawing students' work - their lifedrawings of a model in a World-War-One gas mask: a liferoom made political. Content is foremost for Coe. Form supports and flows from meaning. Kuspitt again: Coe's images can never be "reduced to objects of aesthetic contemplation, as little as Goya's black paintings or Disasters of War." The content is simply too overwhelming.

It might be said that Radio Times stands at one end of illustration's spectrum, and Sue Coe at the other. Decoration/message. Passive/active. Repetition/vision. There are many ways of describing the contrasts between these two extremes -- and ways, too, of showing their connectedness and how they cross over. I have emphasized the one as a negative and the other as a positive because that is my personal response, and I feel strongly that the potential for activist illustration is huge and largely unrealised, and this is in some sense a plea for more of it. Every illustrator negotiates a personal path through alternative ways of working, and perhaps that is the thing to stress rather than the distinctness of the various choices. We constantly speak about either/or in this journal (new versus old technology, Fine Art versus Illustration), but an illustrator's creative voice emerges through a weaving together of any number of whims and personal preferences, and logical consistency is rarely a factor in the way that these choices are made.

For the moment I am sticking with the bias of my argument. Illustration as message art, rather than decoration. In Artists of Radio Times, Martin Baker took a very subjective stance, tracing illustration's pedigree back through "a reassuring continuity of classical practice." But there are darker forbearers also -- broadsides and balladsheets, chapbooks and popular prints, where the world is turned upside down and unorthodoxy celebrated. As Baker points out, the original design of Radio Times is indebted to contemporary comic scripts and theatre programme layout, and both art forms, comics and theatre -- at their subversive best -- are message art: active, vocal, visionary art in the way that Sue Coe shows mainstream illustration can be too.

Sarah Blair November 2002

Notes:

Artists of Radio Times: A Golden Age of British Illustration took place at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, 11 June - 7 August 2002. The catalogue, of the same title, was written by Martin Baker and published by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and Chris Beetles Limited, London.

Sue Coe: An index to Coe's website at Graphic Witness is found at Sue Coe site map

Donald Kuspitt's essay on Coe is from Police State, a catalogue which accompanied a travelling exhibition of works by Sue Coe from 1982-6, published by the Anderson Gallery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia (1987).Text by Mandy Coe.

Love, Labour and Loss is on at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery in Exeter until 4 January 2003. The catalogue, Love, Labour and Loss: 300 Years of British Livestock Farming in Art, is edited by Clive Adams and published by Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle (select link to News from home page).

A successor to After Dolly on the more general issue of intensive farming is currently being planned. To receive details, contact ciwftrust@ciwf.co.uk