ollower.

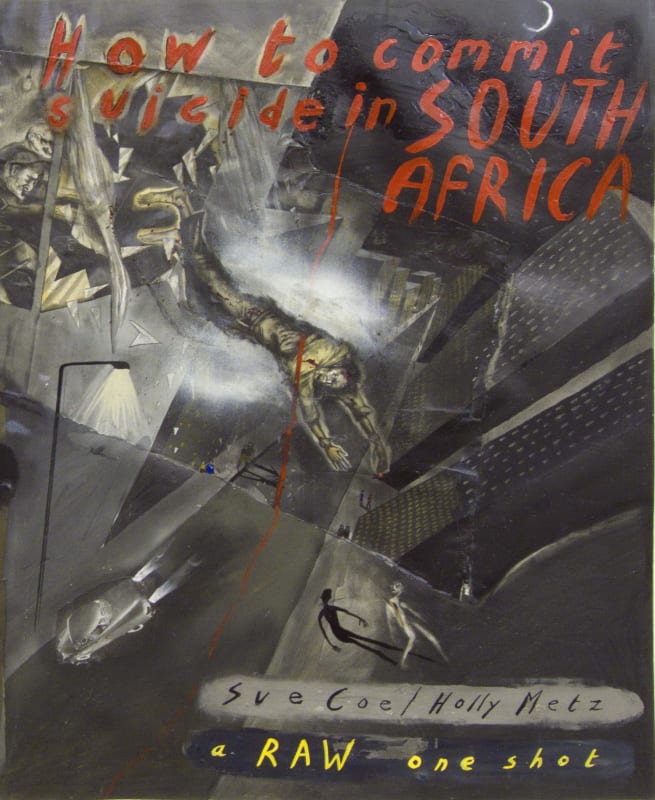

HOW TO COMMIT SUICIDE IN South Africa is an illustrated overview of the tragic reality of South Africa now. It’s a very difficult book to (re-)view because it makes you feel ashamed of being human. This and the symbiotic relationship of Sue Coe’s expressionistic pictures (black, white, slashes of red) with Holly Metz’s factual, well organized, and accessible text transforms what could have been another dreary weekend of agitprop into an outstanding manifestation of creative energy, a successful but chilling union of art and politics.

South Africa is a plantation. A world within itself. A majesty alienated from itself, which symbolically has come to represent deep feelings into which most of us are reluctant to peer—our relationship with a thing we can't control: apartheid. The force of this demonic junction of segregation and supremacism is fully explored in the book, a tabloid format with Metz’s text printed in white letters on black pages. Coe’s intuitive response, her selection of events, and the manner in which those events are illustrated would seem flat and didactic without their saturated involvement in the hard facts of the text.

Coe understands suffering. Her dark, luminous illustrations shimmer in the light of social injustice, particularly “You Can’t Be Too Thin or Too Rich” and “Welcome to Sunny South Africa, the Hot One, Where Every Second Sizzles” (the story of the fire-bombing of a black union-leader’s mother’s house, with the doors and windows wired shut from the outside). If you add “White Republic—No: Peoples Republic” (in Soweto in 1976, an unarmed black student is shot by police) you can see the similarity of Coe’s images to those of other artists who have used suffering as a reference point: to Goya’s The Third of May, 1808, 1814, George Grosz’s Fit for Active Service, 1916–17, and Picasso’s Guernica, 1937. Coe’s use of African masks and animal skulls to cover the faces of South African security forces expresses the movement of primal instincts within contemporary society, the profound relationship of those instincts with nature, and the integral position ritual has in bringing fact and nightmare together. Her familiarity with the source of true power and strength—resistance—is evident throughout.

The essence of Coe’s illustrations is their sheer visual impact. She is a master of narrative realism. The movements of her hand are like maternal gestures or parental consolation—deliberate, forthright; infinite care is placed, with nothing left to chance or weak embrace. Even when stretching illusionistic truth, anatomy, emotion, light and shade, or the laws of physics, Coe’s fluent knowledge of the classical esthetic vocabulary molds her images into open invitations to her remote and yet very accessible world. Accessibility is power. Politics aside, it is Coe’s ability to wield and intertwine classical motifs with contemporary issues that sets How to Commit Suicide in South Africa apart from most artist’s books. Clear vision and command of the technical machinery needed to build unrestricted access for the viewer makes these works important.

Coe’s vicarious relating of past and present is quite evident in the Soweto 1976 piece. A group of men, fixed as in paintings of the deposition of Christ from the cross, huddle around a wounded comrade. Their situation is the result of a hidden but ongoing action, indicated with ominous brevity: two rifle barrels puncture the righthand edge of the page. A barbed-wire fence blocks the only obvious escape route. The emotionally charged postures of the group are heightened by Coe’s pantheistic use of light and shadow. A startlingly naturalistic but eerily unreal bundle of expressions—phlegmatic disdain, angry embarrassment, self-protectiveness, fear, dour expectation—slither out to the viewer from the darkness. In quasi lifelessness, the fallen comrade strains to remain a witness to his almost certain demise. You can almost taste Coe’s salty, grim fascination in her simultaneous emphasis of past, present, and future.

Most of Coe’s pieces are based on actual occurrences. They are a mental list of the ubiquitous characteristics that comprise the relationship between the indigenous South African peoples and their white counterparts. Coe borrows heavily from all aspects of the cultural iconography of these disparate groups and the media’s documentation thereof. In “South Africa,” these rich sources of ideas and imagery occur as masks floating in the vertical borders. Two guards/policemen, wearing similar masks, flog a woman. The gestures and postures of these central figures come from a news photograph which is incorporated into the piece and functions as a seat for our current president. Oddly, Ronald Reagan seems to control the bound woman with a laser/cord (energy source unseen). The masks do more to exaggerate the status of the men than do their uniforms. They are obviously in control of themselves and of that instant in space and time. Two other symbols, the dollar-sign tattoo on Reagan’s cheek and the Nazi arm band worn by one of the guards, show us that we are peering through several layers of meanings, viewing a reality accessible to the point of being transparent.

Coe is a closet lighting technician, and her use of light runs through all the gambits from a clinical application of it, in the clean and well-lit room where some members of the security police force, BOSS, are gently thrashing Steve Biko to death—in an apparent suicide—to its metaphysical embodiment of secret conversation or its ability to emanate from within the subject instead of being reflected inward to the soul. Efficient treachery is the only way to describe Coe’s use of light, and of shadow. Conceptually, black and white is an illusion complete in itself. Its artificial nature points to a remoteness far from the possibility of any intellectual verification, but still closer to the real thing than the real thing. In “Welcome to Sunny South Africa . . . ” Coe isolates the experience of the figures by turning light into solid matter. As flames engulf the house and its residents, the fire calls out to its distant relatives, the comets and meteorites, who don’t come to spend the weekend. The flames fall downward, trying to convince us of the materiality of their photo-plasmic heavenly bodies—well-dressed photons at that. But in reality, it’s Coe’s lightning that unifies these seemingly unrelated groups, both the visible and the invisible. Pleasant dreams.