In 1986, PS1 Contemporary Art Center, as it was then known, held the first solo museum exhibition of Sue Coe’s work in New York. It was titled The Malcolm X Series. Thirty-two years later, as MoMA PS1, the institution now gives Ms. Coe her second solo exhibition in New York, Sue Coe: Graphic Resistance.

Coe’s art takes us on a journey into the heart of darkness; this is the stuff of nightmares and it reinforces our sense of dread in The Age of Trump. The scenes depicted have an underworld feel, with their dark subterranean architectural spaces and sparse artificial illumination. This is the blackest nighttime world we don’t want to know about. All that ego consciousness rejects during the light of day—the torture basement and slaughterhouse—are presented in violent relief, reminding us how a situation can’t manifest externally unless it already exists in the basement of the psyche. There could have been no Hitler without Wotan, the bloodthirsty youth god, who emerged from the mythic cellar. In the painted faces of Coe’s perpetrators, we see mirrored the cast-off dark twin who resides below the threshold of consciousness—what Carl Jung called the shadow. This shadow self may be merged with the worst of the Dionysian excesses Euripides warned us about in The Bacchae, a play he wrote while camped out among the Macedonian legions, surrounded by men not unlike the barbarous Blackwater and ISIS fighters of today. Coe’s is a world of rape, decapitation, dismemberment, disembowelment, gratuitous violence, and toxic masculinity that has been around for a long time. Animals, children, and women are usually the first victims. To think of her work as only political robs it of an important psychological dimension, and fails to acknowledge our part in the drama.

Sue Coe has been at the forefront of much of the political art we see today, drawing terrorists and mercenaries in 1975, a decade before Leon Golub tackled the subject. Death is everywhere in her art, and we think of Freud’s “death drive” and Plato’s “desire for Hades” when seeing Coe’s work, which resonates in our apocalyptic time.

Coe’s art is the powerful protective reaction to an immune system that itself feels threatened, feels itself to be in danger of breaking down, so widespread is the plague of inhumanity that it is responding to. With Coe’s work, art has become humanity’s last line of defense against corrosive social forces. [Donald Kuspit, Sue Coe: Police State, 1987)

When Woman Walks into Bar - Is Raped by Four Men on the Pool Table - While 20 Watch (1983) was shown at MoMA in 1986 as part of the collection of Werner and Elaine Dannheisser, although tucked away in a narrow exit passageway, it stole the show. The bravery of the artist was astonishing even then, as the horror of the piece was as fresh as in the year it was made. Seeing it in 2018, we are confronted with a dark dreamscape, where brutes with popping eyes set upon a fragile skeletal woman. A New York Post headline pictured cries out “SLAUGHTER IN THE SKY Chilling inside story: How Red pilot downed jet and killed 265.” For Coe, rape is a microcosm of the militaristic brutality raining down from the skies on innocents. Skies blackened by swarms of aircraft in works like War (1991) are a reoccurring image and suggest the mutating militarization of endless war. Rape has been with us since antiquity, with the rapes of Persephone, the nymphs, and the Sabine Women. Rape paired with war can reach epidemic proportions, like the Soviet rape of thousands of German women at the end of World War II, and more recently the women and young girls raped by Al-Nusra and Isis. While the “Me Too” movement gains traction, it can be easy to forget that rape and sexual exploitation continue to haunt the fringes of our war-ravaged world.

Sue Coe’s work resonates because it has counterparts in the unconscious, and the mythic depths of the collective psyche. We have only hell when we need something more complex like Chthon, or Hesoid’s Tartarus–that very bottom rung of Hades. Coe surrounds us with phantoms, shades, ghosts, and the undead, who come up from the depths begging for justice. In some of Coe’s works, not seen at P.S.1, images of dead, skinned animals ask a fur clad matron for the return of their pelts, and, in a nightmare writ real, cows, sheep, and chickens haunt the man who has consumed them, and ghostly cows follow a man with a McDonalds bag. In one of this exhibition’s iconic works of a heroic scale, New York 1985 - Car Hookers, Age 13, (1985) a fragile young girl is seen among phantoms rising from sewer lids and floating about. The shades are crying out for our darkest impulses to reach conscious, and for a moral reckoning. Coe roamed the dark alleys of New York City frequented by prostitutes and drug dealers and users, doing research for this work. This is a walkabout that required guts, and she asks us to confront the exploitation of these fragile lost souls.

As a child in Hersham, England, the artist saw a pig that had escaped from a slaughter house near her home and her empathy for the creature set her on a lifelong trajectory. Sue Coe is an animal rights activist in a world we have glimpsed, and then perhaps forgotten, in Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle which exposed the horrific conditions of Chicago’s stockyard’s and meat-packing industry. Dead Meat (1996), Cruel (2012), and The Ghosts of Our Meat (2014), are three books chronicling Coe’s own journeys into these killing sites. Accompanied with essays by such writers as Stephen F. Eisenman in The Ghosts of Our Meat and Alexander Cockburn in Dead Meat, she portrays the cruelty of animal abuse and slaughter with a pathos and potency few artists can equal. We meet her pigs and cows eye to eye, and they become sympathetic and tenderly anthropomorphized like the famous calf on the shoulders of the archaic Moschophoros (Calf-bearer). The artist reminds us that we too are animals and their mistreatment and death may lead to our own. Beautifully drawn animals stare out at us as they are sent to their death in the dehumanized industrialized killing machine. Because cameras are banned in slaughterhouses, Coe takes her seemingly-innocuous sketch pads to record the scenes before her. Slaughterhouse sketchbook, Abu Dhabi, October (2013), and her Porkopolis notes and sketches (1988-1991), give us a remarkable window into this process. The sketches of half-finished hanging carcasses remind the viewer of human executions. Some of her best slaughterhouse works can be seen here, like Slaughterhouse, Tucson (Large) (1989), Scalding Tank (1988), and Dog Food, (1988). Scalding Tank with its rising vapors is as close to a scene in Hades as one can find in the modern era. Dog Food has the creepy feel of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, with its giant, metal factory doors.

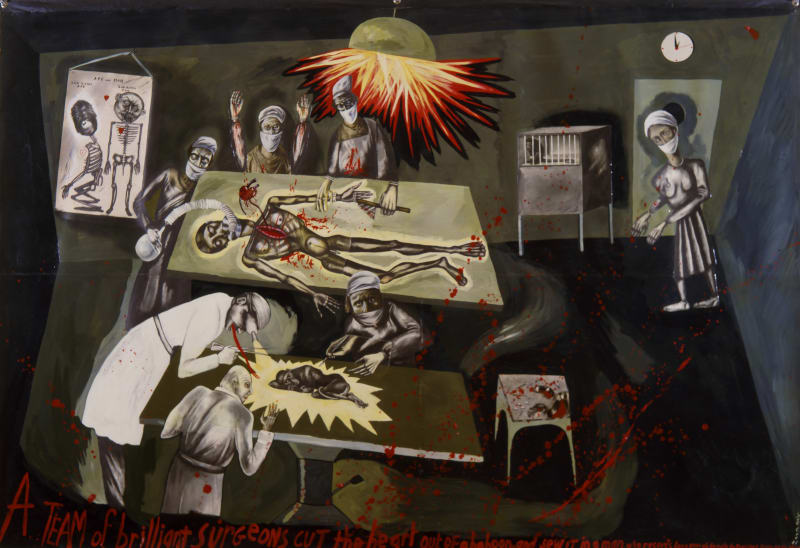

The anti-vivisection works are some of the exhibition’s most haunting, the world of grotesque scientific experimentation gone bad. Baboon Heart Transplant (1984) is based on an actual event: a baboon heart transplanted into a child who died three months later. Here H. G Wells’ 1896 The Island of Doctor Moreau proves to be prophesy, a real-life science fiction horror.

In April, New Yorkers were treated to a group exhibition that included one of Coe’s large-scale paintings at the James Fuentes gallery. The Galerie St. Etienne has mounted stunning solo and group exhibition of the artist’s work over the years including the 1989 Porkopolis: Animals and Industry, the 2000 Tragedy of War, the 2008 Elephants We Must Never Forget, and most recently in 2017/2018’s Käthe Kollwitz and Sue Coe: All Good Art is Political. The MoMA PS1 exhibition consists of some of Coe’s iconic large paintings and a selection of smaller works, with several series shown in flat vitrines, including an array of editorial drawings produced for the New York Times early on in Coe’s career. One vitrine contains a selection of works from a recent series of drawings of zoo animals, soon to be published by AK Press. In Copenhagen Zoo, Denmark: Marius (2017), a giraffe is euthanized and subsequently fed to the zoo’s lions. The giraffe is so tenderly drawn we weep for the gentle creature’s fate. Additionally, the primate drawings in their simplicity are touching studies, much like the graphite Homeless Woman Dressed in Garbage Bags (1992) where a solitary figure floats on a white ground.

Sue Coe shows us a world where the fragile and the disenfranchised of both the human and the animal kingdom are all in great peril. The viewer identifies with these creatures, for we, too are animals she reminds us, confronted by the mechanism of mass slaughter we perpetuate on ourselves and non-human animals in a world ever more dehumanized. In this dark time, Coe’s even darker vision of reality hits us hard. Expanding on a legacy inherited from George Grosz and Otto Dix, Sue Coe takes political and psychological art to new depths.