Sue Coe's colors are the harshest -- black and white, and bleeding red -- and her images are weapons. They claw into your eyes and shove your face in pig gore. Sue Coe isn't kidding. She's targeted the comfortable, the capitalists, the fascists, the racists and the rapists, and anyone who gladly eats chicken, beef or pork. Her fury is authentic. Coe condemns brutality, yet she's sent her art to war.

Two exhibits of her work are currently on view -- at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and at Brody's Gallery, 1706 21st St. NW. The museum's one-room show includes some of her biggest, strongest paintings; the gallery is offering 50 of her prints and drawings. In both these exhibitions, Coe's message is: Repent! She isn't like those artists who love the play of colors or the blue depths of the sky, who look upon God's handiwork and see that it is good. Coe is a dissenter. She sees that it is foul.

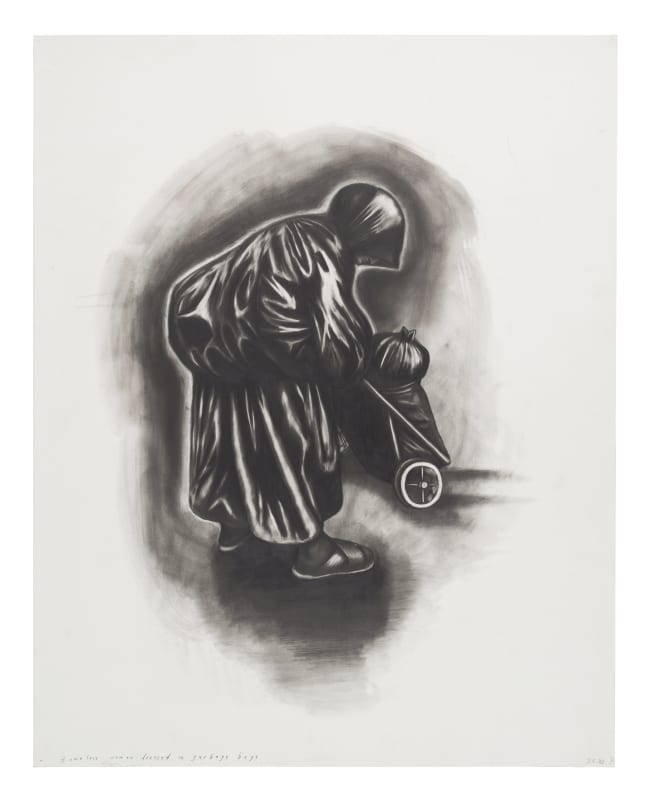

Pigs scream in her "Porkopolis." Her justices are vultures (they're perched on a branch nourished by dark swastikas). Her homeless folk wear garbage bags. The police department choppers in the sky above her "Riot" send down cones of light that call to mind the hoods of the Ku Klux Klan. Her factory-farmed chicks are buried alive. Many of these images were commissioned by the Village Voice, by Time, the New York Times, the Progressive, The New Yorker -- yet somehow one accepts that Coe is not for sale. One believes that she believes.

Her capitalists wear top hats, and their allies look like running dogs. Her soldiers and police aren't protectors of the weak but militarist monsters. Her images aren't subtle. There's a clenched-fist, working-class spirit to her drawing. She's for the revolution, and one print at Brody's commands "Just Say No to Hormone Milk." Her politics might be described as hard-left antivivisectionist. She's a witness -- and a scold -- whose style is a blend of commercial illustration and pounding propaganda, political cartooning and anguished reportage.

What's wrong with her work isn't its message, or that it has a message, for there are many mansions in the house of art, and "Viewing With Alarm" is the old and honored banner flying above one of them. Think of George Grosz and Kathe Kollwitz, Otto Dix and Thomas Nast, all of whom she quotes. No, what's wrong with Sue Coe's work is that it's partially undone by what radicals might call an inherent contradiction. What makes her honest art seem to some degree dishonest is the way it keeps pretending that it isn't art.

"My dream," she told John Yau in 1986, "is that people don't discuss the work but discuss the content." Well, good luck. The sad truth is that content can't be divorced from context. A depiction of the wretched poor hanging in the parlor of, let's say, Ross Perot is not quite the same picture when it's displayed in a hovel. Condemnations of the filthy rich tend to lose their righteousness when shown, as Coe's works used to be, among the shiny ads in Tina Brown's New Yorker.

Something of the sort also happens to Coe's pictures when one sees them at the Hirshhorn -- where dollar signs and art-world chic and something like hypocrisy surround them like a frame.

The artists given solo shows in museums of modern art tend to be the hot ones. Angry art is in these days, as is art-as-politics, and though Coe may hate this truth, may cringe at its suggestions, nonetheless she's hot.

Coe may give away signed etchings to kids from D.C. schools, and may not care for money, but when viewers see her paintings beside million-dollar Rothkos, aren't thoughts of malefactors' wealth bound to impoverish the injunctions of her art?

Coe's pictures may depict a rape victim in New Bedford, Mass., an eviscerated pig or a 13-year-old hooker in Manhattan, but at the Hirshhorn they also depict, by rhyme or by rejection, other works of art. That side of beef, for instance, hanging in Coe's slaughterhouse -- isn't it from Rembrandt? The bending of that figure's back -- doesn't that quote Kollwitz? Coe may want us to imagine the torture of an animal, the horror of a rape -- and maybe she expects us to change our lives accordingly -- but how are we to do so while our minds are grazing the history of art?

When artists seem to be both victors in the money-grubbing, status-driven art world and selfless, leftish saints, how can the viewer help but stumble on the contradiction? Coe's rape painting is a knockout. Her unusually ambiguous scene of Malcolm X standing in the slaughterhouse is branded on your brain. The woman is a drawer, and let's cheer her for that. But still there's something in Coe's art -- in the way that it's delivered, in its uncompromising stance -- that keeps the viewer back.

If you try to ignore context (the steak ads in the magazine, the Rothkos on the wall) and respond to content only, you feel yourself a dupe. And if you take the other tack, and look upon Coe's pictures as fashionable commodities, you have no heart at all. You can't win. You're divided, and she isn't. Perhaps that's why her pictures so often seem to come on holier than thou.

One other nagging question hovers around her shows. If the sexists and the racists and the awful rich are everywhere in charge of the capitalist Establishment, why is it that we so seldom see homophobic screeds, tracts against the homeless, or rightist propaganda in commercial galleries, or in the museums?

Coe's prices, which start at $40 for a print, couldn't be more reasonable. Her howls couldn't be more heartfelt. Her shows close at Brody's on April 15, and at the Hirshhorn on June 19.