Growing up down the street from a slaughterhouse can have a curious effect on one’s life. As a nine-year-old, Sue Coe viewed the local abattoir in Hersham, England, as the factory that put bacon sandwiches on the dinner table. Years later the normalisation of mechanised slaughter, which she encountered on visits to animal killing centres from Liverpool to Los Angeles, became the basis for her most charged graphic work, recently published as the book Dead Meat. Yet it was only after Coe had devoted herself to making political art – confronting rape, police brutality and apartheid – and immersing herself in art’s ethical, moral and ideological implications, that she revisited this childhood recollection as the key to a new, aggressive form of visual commentary that intends to inform and reform.

Coe’s searing examination of animal butchery marks a turning point in her art. ‘I want to know how much that childhood knowledge effects collusion in later life… where one is trained not to question, not to be curious, not to make demands on things that could be wrong,’ she says. Such heightened critique is what differentiates the early from the mature period of Coe’s almost 30-year career as an illustrator, painter and visual essayist, during which she has evolved from a sloganeering propagandist into an articulate social critic.

Art and the class struggle

In the early 1970s, Coe was a pioneer of neo-expressionism in commercial illustration, a movement that began at London’s Royal College of Art and spread to North America. But Coe was not a trendy stylist. Her early work contained seeds of agitation that grew into polemical art, transcending the traditional role of editorial illustration and making its way into an otherwise conservative mass media. Ignoring the constraints of the commercial arena, Coe stubbornly imbued her published work with social and political messages, hoping to inspire others to action.

In the early 1970s, Coe was a pioneer of neo-expressionism in commercial illustration, a movement that began at London’s Royal College of Art and spread to North America. But Coe was not a trendy stylist. Her early work contained seeds of agitation that grew into polemical art, transcending the traditional role of editorial illustration and making its way into an otherwise conservative mass media. Ignoring the constraints of the commercial arena, Coe stubbornly imbued her published work with social and political messages, hoping to inspire others to action.

Coe’s art speaks to the socially oppressed, the disenfranchised and outcast, and addresses people as people, not merely as causes. Her artistic maturity has been forced out of the struggle to balance her (essentially Marxist) politics and a humanist art that searches for deeper meaning. The two are not mutually exclusive, but Coe has often found it difficult to reconcile them within a political framework that insists on art serving the ‘class struggle’.

Despite comparisons frequently made now between Coe and Goya, Daumier, Käthe Kollwitz and others in the pantheon of social and political art, when she first came to New York in 1972 it was easy not to take her too seriously. Although her early editorial illustrations, a cross between Georg Grosz and Richard Lindner, were recognised as the most stylistically provocative in the growing neo-expressionistic genre, her solutions were often too conceptually complex for the editorial problems at hand. Neither realistic mimicry of texts nor clever cartoon interpretations, her images were disturbing, symbolic juxtapositions of anthropomorphic characters or people with sharp, edgy features, who looked like gargoyles. American art directors appreciated her raw style, but they were dubious about what appeared to be her work’s polemical content. In fact it was less polemical than they thought: Coe’s symbolism reflected her bewilderment with the endless parade of haves and have-nots that she encountered after spending weeks around Harlem and Times Square. Sitting in the afternoon audience for television quiz shows became the basis for an early satire of how Americans humiliate themselves for money.

Coe chronicled what she saw on the street in sketchbooks and incorporated it into jobs for The New York Times Magazine and the newspaper’s op-ed page. The censorious nature of commercial illustration forced her to compromise at every turn, although she was more adamant than most illustrators about refusing to make too many editorial changes. (Once I saw her tear a drawing in half when an art director demanded unacceptable alterations.) For years she got enough editorial work to make a living, and some of the illustrations were accepted in annuals, making her influential among young would-be neo-expressionists. Art directors, however, saw her as a kind of exotic outsider and she still recalls being treated condescendingly, especially by successful male illustrators, who sarcastically dismissed her ideas as ‘Sue Coe’s working-class rage’. Coe did not fit the profile of an American Illustrator.

Unlike the average art school student in the United States, she came from a working-class family. She was born in 1951 in Tamworth, near Birmingham, and when she was young her family first moved to London, then out to the suburb of Hersham and, later, Walton on Thames. Her mother had gone to a small art school before leaving to get a job, and Coe and her sister Mandy, were given brushes and paints for Christmas and birthdays. ‘Art was part of me since the genetic code was fermenting,’ says Coe. ‘But the idea that I could earn a living from it was absurd.’

Her parents insisted that she learn a trade, so at fifteen years old she took shorthand classes in school (which proved disastrous) and spent the next two years working off and on in a factory. Her options were to get married, work as a secretary, or become an artist. At seventeen she disobeyed her parents and joined a foundation course at Guildford School of Art. At eighteen she went to Chelsea School of Art, earning a BA, after only two years, in 1970. She was urged by one of her teachers to apply to London’s Royal College of Art to do an MA. The age limit was 21, so she lied to get in.

Stylised disasters

When Coe was accepted at the RCA the times were socially tumultuous; it was the era of the working-class hero. She recalls that the students were politicised by the Vietnam War, but theirs was the politics of general anger, not a specific ideology. While she and her fellow students participated in protest marches, her drawings were not polemic. She admired the expatriate African American political cartoonist Ollie Harrington and the social printmaker Richard Wright, yet her major influences were teachers Eduardo Paolozzi and Peter Blake, who encouraged the release of pent-up personal expression in Coe and other students.

When Coe was accepted at the RCA the times were socially tumultuous; it was the era of the working-class hero. She recalls that the students were politicised by the Vietnam War, but theirs was the politics of general anger, not a specific ideology. While she and her fellow students participated in protest marches, her drawings were not polemic. She admired the expatriate African American political cartoonist Ollie Harrington and the social printmaker Richard Wright, yet her major influences were teachers Eduardo Paolozzi and Peter Blake, who encouraged the release of pent-up personal expression in Coe and other students.

The painters David Hockney and R. B. Kitaj, who had made their mark while students at the RCA in the early 1960s, also influenced a re-evaluation of style and content. Hockney’s Rake’s Progress had a significant impact. ‘His draftsmanship was very working-class,’ says Coe. ‘It wasn’t just a few abstract smears that middle-class people could get away with. It was so laboured over, it was inherent there was some content.’

Coe’s colleagues were more influential than the old-school RCA teachers. She was a key member of a group of students who combined a kind of hippy and proto-punk disdain for the establishment in a mannerism that would forever alter the style of illustration from realistic objectivism to personal expressionism: Coe, Stewart Mackinnon, Terry Dowling and the Quay Brothers were exemplars of the new art brut.

Coe spent her first year rebelling against the mostly ‘well meaning teachers from wealthy families’ by painting apocalyptic scenes instead of neat illustrations for children’s books and editorial pages. ‘I gave them a crashing plane for every assignment,’ she says. Her drawings were also being published in Nova and The Times, both mainstream outlets for experimental work, and she was illustrating covers for Penguin Books. But lack of college support for what she was doing led her to ask for dispensation from the RCA to go to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and otherwise complete her MA independently in New York. She spent only one day at Pratt, but earned her degree anyway in 1973.

American nightmares

The collection of stylised air disasters got Coe her first American commissions. The first was assigned by Milton Glaser, design director at New York Magazine, and then killed by him when he found the work (the subject of which Coe cannot remember) too abstract. For the second, commissioned by Ruth Ansel at The New York Times Magazine, she adapted the compositional format of the airplane cockpit as the interior of a submerged submarine for an article about the ownership of oceanic trade rights. ‘The editors asked for more fish, more fish, more fish, and then I got my money,’ she remembers.

Coe also found feminism in New York. Then she was mugged and began drawing pictures about rape victims. ‘I was politically minded but it never occurred to me to put it in my artwork,’ she says. She received more illustration assignments, but since there were long periods without any work she decided to take an active role as a volunteer in poor communities, and was drawn to the American Communist Party in New York, where the Workshop for People’s Art produced posters for tenant strikes and block organisations. ‘This experience helped me understand what works and what doesn’t,’ she says. ‘Funky English punk art does not work in a tenant / landlord struggle. The art school mentality is not effective with people who don’t have the luxury of trying out artistic styles, of breaking up a picture. What does work is a very realistic depiction of that struggle.’

Coe turned from abstraction and allegory to a gritty social realism – ‘gutter journalism’, as she terms it – that allowed her to report and comment on the turmoil in the street as well as her favourite theme, the decay of the bourgeoisie. ‘I have an intense curiosity about how the economic crime of capitalism impacts on people,’ she says. This became the single most ubiquitous idea running through her early work.

In search of a grand manner

Coe’s variant of social realism did not follow the Soviet model of styleless, generic heroism, nor an American mural style of historical optimism. Rather her vocabulary was characterised by what art critic Donald Kuspit calls ‘synthesising Expressionist and Surrealist methods in a search for a grand manner’ – a baroque manner with ‘snatches of representation’. Here the historical models are useful. Like Goya and the seventeenth-century etcher Jacques Callot she isolated vignettes of horror; like Daumier and Grosz she made totems out of the commonplace; and like Rivera and Orozco she froze the historical moment. Consistent with traditional propaganda, Coe has always been unambiguous about good and evil; her oppressed are confined to cocoons of despair and the oppressors are given monstrous physical traits (fatheads with phallic tongues; capitalists with the heads of vicious sharks). Yet even her single-image tableaux, as opposed to her later lengthier essays, contain multiple levels of meaning, sandwiched between realistic representation. Moreover, Coe’s pictures are charged by a dark palette with spots of blood red contrasted against less vivid blues, greens, and yellows. In the manner of Bosch, she pays detailed attention to the environments in which her protagonists are situated. And often, ironic wit is skilfully used.

Coe’s variant of social realism did not follow the Soviet model of styleless, generic heroism, nor an American mural style of historical optimism. Rather her vocabulary was characterised by what art critic Donald Kuspit calls ‘synthesising Expressionist and Surrealist methods in a search for a grand manner’ – a baroque manner with ‘snatches of representation’. Here the historical models are useful. Like Goya and the seventeenth-century etcher Jacques Callot she isolated vignettes of horror; like Daumier and Grosz she made totems out of the commonplace; and like Rivera and Orozco she froze the historical moment. Consistent with traditional propaganda, Coe has always been unambiguous about good and evil; her oppressed are confined to cocoons of despair and the oppressors are given monstrous physical traits (fatheads with phallic tongues; capitalists with the heads of vicious sharks). Yet even her single-image tableaux, as opposed to her later lengthier essays, contain multiple levels of meaning, sandwiched between realistic representation. Moreover, Coe’s pictures are charged by a dark palette with spots of blood red contrasted against less vivid blues, greens, and yellows. In the manner of Bosch, she pays detailed attention to the environments in which her protagonists are situated. And often, ironic wit is skilfully used.

For some critics, however, Coe’s polemic images from the late 1970s and 1980s are shrill ideological slogans. One critic writing in Art in America judged her treatment of rape, drugs and class struggle to be ‘slightly naive and one-dimensional’. It is true that Coe often uses stereotypes to communicate an idea easily, and the dogmatic traits in her work are more apparent when she is forced by choice or circumstance to encapsulate complex issues into what becomes a political cartoon. Since editorial cartooning requires an artist to think and render quickly, often pounding a profound idea into a joke, this is not one of Coe’s best metiers; she seems compelled to overwork, or even overstate the issues.

She is continually hit by criticism of her work from both sides of the ideological spectrum. Recalling her early bouts with the Communist Party, she says that her co-workers did not care about her as an artist, and in public forums condemned what they perceived to be bourgeois tendencies or stylistic mannerisms in her work. A few male comrades went so far as to challenge the depiction of rapists as monsters, admonishing her for presenting derogatory images of working-class men. When Coe countered that the Ku Klux Klan are working-class men too, the critics reproached her for a lack of true working-class analysis.

More recently she was attacked for a depiction of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas climbing to the pinnacle of his career over a heap of black men, on the grounds that no black man – however reactionary – should be criticised by ruling-class standards. ‘I thought I had made a strong political statement,’ says Coe. ‘But when I did the drawing I was a white person talking to white people at a level of arrogance completely removed from the idea that black people can look at this too. I thought I was politically astute but I wasn’t. So I need people to tell me.’

Nevertheless, she accepts only that which she believes is true. ‘I understand the push and pull between developing as an artist-in-the-struggle and going beyond the limits of acceptability . . . I’m my own motor now. But I realise that a big problem with art is that the artist is too much into what the artist wants to say. There has to be a balance.’ Like Käthe Kollwitz, who devoted her life’s work to maintaining ideological accessibility, Coe sometimes laments that she too is unable to create an abstract image or tackle an optimistic scene. ‘Sometimes the struggle demands showing forward movement,’ she confesses. ‘I’ve tried it, but it just doesn’t sit well with me.’

Commercial approach

Coe is devoted to the opposition, yet consciously works for instruments of the system. ‘We live in capitalism. So what is one prepared to do to earn a living?’ she asks rhetorically. Coe is prepared to make commercial illustration provided she can get a fair number of uncompromised images into print. A relationship is maintained with The New York Times and The New Yorker where, within certain bounds, she has been able to make visual statements against venality. ‘I do all my work for reproduction, for the masses, for the millions of people who read newspapers and magazines,’ she says, ‘and not just for the few who come to art galleries.’

Coe is devoted to the opposition, yet consciously works for instruments of the system. ‘We live in capitalism. So what is one prepared to do to earn a living?’ she asks rhetorically. Coe is prepared to make commercial illustration provided she can get a fair number of uncompromised images into print. A relationship is maintained with The New York Times and The New Yorker where, within certain bounds, she has been able to make visual statements against venality. ‘I do all my work for reproduction, for the masses, for the millions of people who read newspapers and magazines,’ she says, ‘and not just for the few who come to art galleries.’

‘The art world is a zipped-up body bag of what they call culture,’ Coe asserts. But in the early 1980s, coincident with the rise of Reaganism, art galleries that addressed the concerns of gays, African Americans and women began to open in working-class areas, especially on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Coe had amassed a huge inventory of unpublished work and the first gallery to, as Coe puts it, ‘trawl for stuff they could sell’ was PPOW (owned by Penny Pilkington and Wendy Olsen), which became known for exhibiting socially conscious art. Coe was also invited to exhibit at PSI, the critically acclaimed alternative art space, which allowed her to show her twenty-foot rape paintings. Among them was a brutal picture of a gang rape called Woman Walks into Bar – Is Raped by 4 Men on the Pool Table – While 20 Watch, which depicts a woman splayed on a pool table in a New Bedford, Massachusetts bar.

Within a short period, Coe went from being ignored to celebrated by the art community. Critics equated her with Beckmann, Posada and Siqueiros. In 1987, Art News put her on its cover. Her work was acquired by private collectors and museums. She was taken on by Galerie St Etienne in New York, known mostly for exhibiting German and Austrian Expressionists, and Grandma Moses. In 1994, she was honoured with a retrospective at Washington’s Hirshorn Museum, part of the Smithsonian Institution.

A changing reality

Why had culture caught up with Coe? As social conditions worsened in North America in the 1980s, the work she began in the 1970s began to touch nerves among the middle-class. The indifference of the ruling class had been a recurring theme in Coe’s work, and it acquired more resonance when AIDS and homelessness entered the middle-class reality. As interest in her work increased, she began to explore alternative means of getting the message out, using the book in particular as a medium for commentary.

Why had culture caught up with Coe? As social conditions worsened in North America in the 1980s, the work she began in the 1970s began to touch nerves among the middle-class. The indifference of the ruling class had been a recurring theme in Coe’s work, and it acquired more resonance when AIDS and homelessness entered the middle-class reality. As interest in her work increased, she began to explore alternative means of getting the message out, using the book in particular as a medium for commentary.

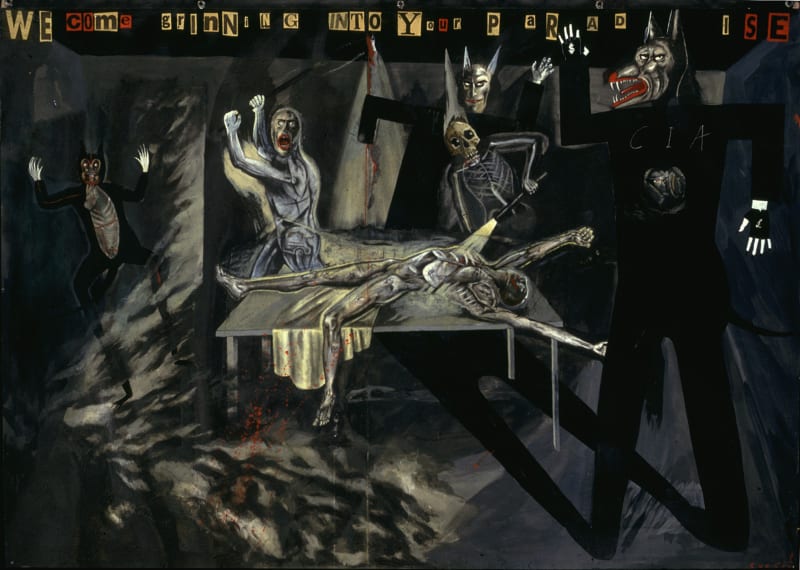

Her first book, a journalistic exposé entitled How To Commit Suicide In South Africa, by Sue Coe and Holly Metz, was published by Raw Books and Graphics in 1983. It was an investigation into apartheid inspired by the murder in prison of the black South African activist Steve Biko, which wove together interpretive visual impressions with factual accounts from newspapers. ‘Holly and I wanted to make a record of all the people who died in detention who supposedly committed suicide,’ Coe explains. ‘We both believe that if people know the facts, they’ll change the system.’ Along with economic servitude, torture was the government’s most powerful weapon against the oppressed majority. Coe created images such as We Come Grinning Into Your Paradise, showing a male figure on a torture table that represents the South African homeland. Under translucent skin appear insects denoting social and moral decay; five sadistic monsters represent the power and greed of the enslavers. As with most of her images, the viewer is forced to follow the details of the picture as you would a road map, before reaching the destination, or core, of the message. ‘The frightening surrealism of this dark portrait brings alive the physical substance of often-overlooked headlines,’ wrote Frank Gettings in the catalogue of the Hishorn retrospective.

The multi-picture essay, consisting of related images in a more or less contiguous narrative combined with text, became an effective way to address complex themes in more depth, and to avoid the use of stereotypes that had stalled her earlier work. How to Commit Suicide in South Africa was successful enough to be republished in a number of editions. For Coe, however, the most significant critique of it came from a black friend who said it was not really examining his struggle in America. In her second book X, also originally published by Raw Books and Graphics, in 1986, as a visual complement to the Autobiography of Malcolm X, she tried to address the struggle of African Americans. X contains images (originally shown at PSI) of Malcolm X alongside grotesque representations of J. Edgar Hoover’s witch-hunts and the Klu Klux Klan, and caricatures of Reagan and the ‘sharks of Wall Street’.

In retrospect Coe is harshly critical of her own work. ‘No one told me, but this was a mistake,’ she admits. ‘It is too easy to say that I’m not black, and therefore do not understand the black struggle – that is like men saying they can’t be affected by sexism. But I made Malcolm into an icon when I should have dealt with him as an individual.’ While X was graphically impressive, Coe’s overall message about government oppression of African Americans had the shrill tone of her earlier more cartoon-like work.

Since then Coe has attempted to imbue her essays with what she calls more humanist imagery, or pictures she describes as showing optimistic, though not falsely optimistic, visions of the struggle. With How to Commit Suicide in South Africa, she recalls that editors Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly convinced her that the humanist pictures were unnecessary. ‘That wouldn’t happen now, I am much more self-assured,’ she insists. Spiegelman, however, describes Coe’s humanistic pictures as ‘the Keane eyes problem’, referring to the schmaltzy 1950s painter of doe-eyed children. ‘Sue does not want to be admired only in her negativity,’ he says. ‘So she comes up with the soulful victim infused with all the warmth she can muster. The fact is, she’s better fighting against sentimentality; when you deal with the angry stuff, the honest sentiment comes out.’

Spiegelman believes that Coe’s need to make heroes out of revolutionaries is a superego desire to make a resoundingly positive statement, and perhaps at the same time create an official art of the struggle. But Coe is best when her anger is directed towards change. ‘It is more useful to posit the negative,’ continues Spiegelman. ‘than theoretically posit the positive, since there’s nothing to attack. Even Milton found it was easier to have the devil do his bidding than Jehovah.’

Descents into hell

In 1987, a childhood memory of the slaughterhouse down the road inspired a new way of looking that launched a modern-day, Miltonian descent into hell. After nine years of visiting abattoirs throughout the world (sometimes without permission), she published Dead Meat this year. Its 160 images are a first-hand account of institutional butchery. Like Upton Sinclair’s 1906 protest novel about the Chicago stockyards, The Jungle, it represents a significant historical record of a prevailing practice. But Coe’s visual indictment is more than an animal rights diatribe. While it spares us nothing in its depiction of animals in torment, it also offers an insight into the workers’ conditions that is compassionate and ultimately, perhaps, cathartic. The reader will draw a connection between animal slaughter and human genocide, which was one of the early motivations for pursuing this theme. Yet Coe’s work should not be confused with a Holocaust allegory. This is social realism, but more important, it is a study in moral contradiction. Coe hates the work carried out in the abattoir, but respects the workers who she portrays as human beings not demons.

In 1987, a childhood memory of the slaughterhouse down the road inspired a new way of looking that launched a modern-day, Miltonian descent into hell. After nine years of visiting abattoirs throughout the world (sometimes without permission), she published Dead Meat this year. Its 160 images are a first-hand account of institutional butchery. Like Upton Sinclair’s 1906 protest novel about the Chicago stockyards, The Jungle, it represents a significant historical record of a prevailing practice. But Coe’s visual indictment is more than an animal rights diatribe. While it spares us nothing in its depiction of animals in torment, it also offers an insight into the workers’ conditions that is compassionate and ultimately, perhaps, cathartic. The reader will draw a connection between animal slaughter and human genocide, which was one of the early motivations for pursuing this theme. Yet Coe’s work should not be confused with a Holocaust allegory. This is social realism, but more important, it is a study in moral contradiction. Coe hates the work carried out in the abattoir, but respects the workers who she portrays as human beings not demons.

Coe’s position as an eyewitness reporter imbues this work with a moral authority that is lacking in her heartfelt but more vicarious pieces. In addition to unforgettably detailed descriptions of electrocution and sticking, the scalding vat and the scraping machine, Coe has produced a document of such rare eloquence in the history of art that it is deserving of comparison to Goya’s Disasters of War.

Her images are based on a clarity and descriptive accuracy that is tinged with anthropomorphic identification. The pig’s-eye-view is an effective trope for exacting empathy. As cathartic are Coe’s entries in her journals, like this about a cow in the knocking pen: ‘Once her head was raised enough to see outside the box, but having seen the terrible sight of hanging corpses – it fell back again. All the noise is of the dripping blood and FM radio playing . . . It is The Doors – a complete album side. I start to draw – and occasionally look back at the box to see her still breathing. Then I look again – I see the weight of her body has forced the milk from her udders, and it starts to flow in a small stream along with the blood . . . blood and milk go down the drain. I look up and see that none of the cows had been milked, their udders are still full.’ Coe’s written accounts give this epic a credibility that other homilies often fail to achieve. She does not rub the audience’s face in her experience. Neither does she call for impossible reforms, but for more humane conditions for animals and workers. Dead Meat relies almost entirely on the truth of the event without succumbing to the ego of the artist. ‘When the content is that profound, it’s not about me as the artist,’ she says. ‘It’s about the vision of those people and animals, and has to be recorded in the essence of humility. The more I’m in those situations, the more the style drops away.’

Her next project was a series of portraits of terminally ill AIDS patients at the University of Texas at Galveston Teaching Hospital, administered by Dr Eric Avery, a physician and artist. Pictures with simple titles – Paul, Louis, Gary’s Last Portrait – reject artifice in favour of compassion. This record of men in the final stages of life is both a document of this century’s scourge and a testament to the dignity of both those who suffer and treat it. One particularly moving drawing, It’s Over, shows a physician admitting defeat as he removes the body of a man from bed to gurney. Political art cannot be any more eloquent than this.

On a wall in Coe’s live-in studio is a 5ft x 6ft 4in painting called Ship of Fools. Though characteristically dark, it is nonetheless more colourful than her other work, and more detailed. It took over a year to complete. This is the artist at her most playful, at times whimsical, and even sentimental. But as an allegorical composite of all the betes noires, venalities and human concerns that have obsessed her since coming to America 25 years ago, Ship of Fools signals another of Coe’s passages, this time from maturity to wisdom. It is also proof of her commitment to the struggle that she adopted and has never betrayed.

Coe has lost none of her anger, but she has learned how to control it. It is the anger that has given her the strength to experience atrocity and horror, and emerge ennobled. It is the anger, as well as the compassion and commitment, that allows her to bear witness when most of us are too timid even to get involved.

Steven Heller, design writer and editor of the AIGA Journal, New York

First published in Eye no. 21 vol. 6, 1996